| Click above to watch the content of this web site in video form. After watching the eighty-six minutes in the playlist (which consists of six segments), you will have seen all of the material on this site, except for a small number of items identified in the text portion of the web site as “Web Bonus Content and the contents of the Appendices page.” [Following playback of the six-part series, the playlist will continue with a seventh video (running under two minutes) which is not part of the series but supplements one aspect of it.] Those who prefer to read rather than listen to the narration in the video, can get the same facts by remaining on this page and continuing with the succeeding pages. Visitors who experience the content in this way won’t miss the film clips interspersed within the full video, because the film clips have been isolated for one-subject playback and have been placed between the same text passages as where the clips appear in the full video. Most citations for newspaper clippings, and all identifying information for the film clips, are omitted in the videos. Viewers of the full video who want to know the source of a particular item, should come to the text pages to obtain the desired citations. |

Actors Chosen for Ayn Rand Roles

This web site is divided into four main pages plus a page of appendices.

Use this navigation pane to go directly to a particular page.

1. • Ayn Rand’s Early Hollywood Years

• “Night of January 16th” under its original Broadway producer . . . . go there

2. • “Night of January 16th” as a movie

• We the Living adapted for Broadway . . . . current page

3. • Ayn Rand returns triumphantly to Hollywood . . . . go there

4. • Other “Night of January 16th” productions

• Juries and Jurors

• Cast ideas for Rand’s Magnum Opus . . . . go there

Appendices. Contents include: the proper title for “Night of January 16th,”

Ayn Rand’s cast choices for Atlas Shrugged,

and further information about the actors discussed in the main pages . . . . go there

| ||| | ||| | ||||

“Night of January 16th” as a movie and

|

|||||

| With “Night of January 16th” an established hit Broadway play, a movie of it was a good commercial prospect, more so than when MGM had that opportunity while the title was “Penthouse Legend.” The sale of the rights didn’t occur as quickly as usually the case, because Al Woods didn’t put them on the market early on; he sought to form his own movie company to produce movie adaptations of this play and subsequent plays. Two years later, he made a conventional sale. image: Los Angeles Times, March 16, 1936, pg. 13 Note: Clarification as to whether the title of the play is properly “The Night of January 16” or “Night of January 16th” is discussed in an appendix to this site. |

|

||||

|

RKO bought the rights, seeking the very popular Claudette Colbert to star in it. image: The New York Times, June 22, 1938, pg. 27

Colbert could play gutsy and self-protective, wise and feminine, unwilling to be made fool of. |

|

|||

[Explaining what occurs at a change of scene within the video, the following comment is made in the narration:] Colbert accompanies the reporter as he itemizes historic artifacts inside an old ship. Those familiar with the play “Night of January 16th” and who remember what occurred between Karen Andre and her employer the night they met, might be fascinated by how Colbert plays this scene. film source: Claudette Colbert in I Cover the Waterfront (1933), with Ben Lyon |

|||||

| RKO was planning to begin filming with Claudette Colbert in August 1938. Colbert’s salary was then the highest of any actress. Colbert was the highest-paid woman in American several years in a row. image: Hartford Courant, July 24, 1938, pg. A6 |

|

||||

| RKO didn’t go into production that year, but on the last day of 1938 this report appeared that a producer was assigned, writers about to be named, and Colbert still to star. image: The New York Times, December 31, 1938, pg. A7 |

|

||||

| Two days later, a headline announced the same plan about Colbert. image: Los Angeles Times, January 2, 1939, pg. A10 |

|

||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| One year and seven days after Ayn Rand put her signature on a contract to sell movie rights to “Night of January 16th” to RKO, another contract became binding by which RKO sold those same rights to Paramount. As of July 20, 1939, Paramount has owned the movie rights. image: contract dated July 13, 1938 signed by Ayn Rand by which she sold movie rights to RKO for Penthouse Legend. The gray line separates content which appeared on separate pages in the full two-page agreement. Admittedly, the image quality is poor. The image here was copied from a PDF made from a microfilm shot from originals of which the contract seems to have been represented by a fuzzy photocopy. I reason this because the adjacent images on the microfilm are much sharper, suggesting that they were microfilmed from originals while the contract was not.

|

|

||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

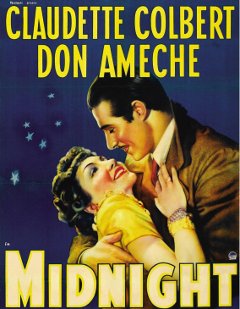

| Paramount made arrangements with 20th Century-Fox for Don Ameche to star in “Night of January 16th”. This could have resulted in a combination of Claudette Colbert and Don Ameche topping the cast, a combination that worked well in Paramount’s superb 1939 champagne comedy Midnight. |  |

||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| Ayn Rand was in New York, where she had adapted her 1936 novel We the Living into a play about to be produced titled “The Unconquered.” image: The New York Times, December 1, 1939, pg. 26 |

|

||||

| Dean Jagger was cast as Andre opposite the play’s star, Eugenie Leontovich. Onslow Stevens was cast as the lead Russian aristocrat, Leo. image: Christian Science Monitor, December 14, 1939, pg. 18 |

|

||||

| Other members of “The Unconquered” cast were named in a December 21, 1939, story; the story correctly notes that the last on the list, Frank O’Connor, is Ayn Rand’s husband. image: The New York Times, December 21, 1939, pg. 28 |

|

||||

| Two days later, an ad appeared in the Baltimore Sun, as Baltimore is the city where the played tried out before heading to Broadway. image: Baltimore Sun, December 23, 1939, pg. 11 |

|

||||

| This December 24 Baltimore Sun ad names the three lead actors: Leontovich, Jagger, Stevens. image: Baltimore Sun, December 24, 1939, pg. MS10 |

|

||||

| The Baltimore Sun ran a story about the play on December 24 with this photo of Eugenie Leontovich and Onslow Stevens in the roles of Kira and Leo. image: Baltimore Sun, December 24, 1939, pg. MS10 |

|

||||

| In a film the year before Onslow Stevens played Leo, we see how Stevens played a role of proud bearing and unique ambitions. film source: Onslow Stevens in Life Returns (1938) |

|||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| Dean Jagger demonstrates in a 1936 film how he could play a character in a leadership position, one who cultivates a ruthless disposition, and suffers his lover’s scorn. film source: Dean Jagger in Revolt of the Zombies (1936) |

|||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||||||||||||||

| On January 18, 1940, the Baltimore engagement having long closed, The New York Times carried this report that Eugenie Leontovich had been replaced by Helen Craig. image: The New York Times, January 18, 1940, pg. 27 |

|

||||||||||||||||

| Helen Craig didn’t start making movies until the end of the decade. This photograph is from one of her few films before she left the film medium long-term; she waited to turn again to movies and television over two decades later. image: Helen Craig in The Snake Pit (1948) |

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Variety also did a story saying that while Kira was being played by Eugenie Leontovich, the lead had been miscast. images: (left) Variety, January 10, 1940, pg. 34; |

|

|||||||||||||||

|

“The Unconquered” opened mid-February on Broadway to a very short run and bad reviews. Dean Jagger was the only cast member among the top three roles to be retained from the Baltimore production. images: (left) The New York Times, February 14, 1940, pg. 28; |

|

|||||||||||||||

[The following remarks are spoken as narration during the video:] John Emery graced the stage of “The Unconquered” as Leo during the Broadway run of February 13 to 17, 1940. We’re seeing him two years later. The actress in this scene is Ann Harding, one of those thought of by Al Woods when casting Karen Andre for the Broadway production of “The Night of January 16.” film source: John Emery in Eyes in the Night (1942), with Ann Harding Note: A heavily-detailed account of bringing “The Unconquered” to stage—going into such matters as contracts, Rand’s interactions with the director, and sets—covers a dozen pages in Jeff Britting’s essay “Adapting We the Living,” in Essays on Ayn Rand’s “We the Living”, edited by Robert Mayhew (Lexington Books, 2004/2012), chapter 8 (first edition), chapter 9 (second edition). |

|||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||||||||||||||

| Back in Hollywood, reports emerged February 12th that Barbara Stanwyck would play opposite Don Ameche for Paramount in the movie of “Night of January 16.” image: The New York Times, February 12, 1940, pg. 19 |

|

||||||||||||||||

| This is the same Barbara Stanwyck whom Al Woods had thought of for the Broadway production five years earlier. film source: Barbara Stanwyck in Meet John Doe (1941) |

|||||||||||||||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| Another story the same day likewise reported that Stanwyck was in where Colbert was out, but added that a top director was assigned (Mitchell Leisen), and that seven years earlier RKO could have bought the rights cheap when Ayn Rand was working in the studio’s wardrobe department, but that instead RKO paid big money before selling to Paramount. image: Los Angeles Times, February 12, 1940, pg. 11 |

|

||||

| Two months later, the Hollywood Reporter disclosed that Don Ameche refused to play Guts Regan and was being sued. Later stories reported that Ameche was always concerned to convey an upright image and did not want to play a brutal character. image: Hollywood Reporter, April 10, 1940 Documentation about Ameche’s concerns appear below. |

|

||||

| A month and a half later, on May 23rd and 24th, two stories told readers that there were now two cast changes in the top two roles—again, two big stars: Paulette Goddard and Ray Milland. The title was changed again: it was to be “Secrets of a Secretary.” image: The New York Times, May 23, 1940, pg. 31 |

|

||||

|

In the May 24th story, syndicated columnist Louella Parsons asked why change the title when the play was a hit. She said it was “a darn good play.” The Don Ameche lawsuit was ongoing, she reported. image: Washington Post, May 24, 1940, pg. 12 |

||||

|

|

||||

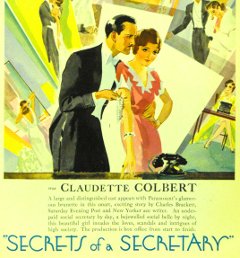

| Paramount had nine years earlier made a movie called Secrets of a Secretary, and had Claudette Colbert starred in the adaptation of “Night of January 16th” under the planned new title for the movie, it would have meant she would have starred in two movies titled Secrets of a Secretary that otherwise would be different. | |||||

images: color ad for Secrets of a Secretary in the Motion Picture Herald, May 2, 1931; black-and-white ad for Secrets of a Secretary in the Motion Picture Herald, 1931. |

|||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| Back when Ayn Rand had contracted with MGM to adapt “Night of January 16th” for Myrna Loy—back when the only title for it was “Penthouse Legend”—Myrna Loy would have potentially made two movies back-to-back, with the same or similar titles. Myrna Loy, at the very time of Film Daily reported in its August 11th issue that just-plain Penthouse had recently finished filming. The Hollywood Reporter carried a review of the completed, edited Penthouse movie in its August 22 issue, and the movie was in theaters September 8. image: Weekly Variety, July 25, 1933, pg. 7 |

|

||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| With so much occurring from July 25 to September 8, it couldn’t have happened that Ayn Rand’s story “Penthouse Legend” could have provided the basis for the movie MGM released as Penthouse six weeks later —despite what a respected film-information resource says. | This respected film-information resource provides citations to trade papers indicating that “Penthouse Legend” was Ayn Rand’s original idea whereas just-plain Penthouse is from a story by one Arthur Somers Roche—more reason to recognize that the two project were unrelated except for similar titles and the same leading lady. | ||||

images: (left) Hollywood Reporter, August 4, 1933, pg. 4; |

|

||||

image: review of the completed film Penthouse in Hollywood Reporter, August 22, 1933, pg. 6. Note the date in the upper right, which is not even a month later than the announcement that Ayn Rand had been engaged to write. |

|

||||

|

Had Colbert made both a Secrets of a Secretary in 1931 and another “Secrets of a Secretary” in 1940, with different stories, it would have been no different than John Wayne making both The New Frontier in 1935 and New Frontier in 1939—with different stories. But that happened. | ||||

| Had Myrna Loy followed Penthouse from Roche’s story with “Penthouse Legend” from Ayn Rand’s story, it would have been comparable to Alfred Hitchcock filming W. Somerset Maugham’s story “Ashenden” in 1936 as Secret Agent and then later that same year filming Joseph Conrad’s story “The Secret Agent” as Sabotage. |  |

||||

| Don Ameche settled with Paramount; he would play a role originally intended for Ray Milland whereas Ray Milland would play the role Ameche refused. image: The New York Times, September 17, 1940, pg. 33 |

|

||||

[The following remarks are spoken as narration during the video:] Ray Milland had been playing lead roles in murder mysteries and light comedies. You’re about to see him avow the value of his life. We’re see him three years earlier. (In 1940, he was still five years from surprising Hollywood with his Academy Award-winning role as an alcoholic in The Lost Weekend.) film source: Ray Milland in Bulldog Drummond Escapes (1937), with Porter Hall (with gun) and Heather Angel |

|||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| Paulette Goddard could exude joy and pleasantness, but also get feisty when she fought for her values. film source: Paulette Goddard in Pot O’Gold (1941) |

|||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| At the end of December 1940, Brian Donlevy was being named for the male lead of “Night of January 16th.” Though not bearing a name remembered as a star, Brian Donlevy was a very good actor. image: The New York Times, December 30, 1940, pg. 20 |

|

||||

film source: Brian Donlevy in Impact (1949) I approve Donlevy. |

|||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| That same day at the end of December 1940, Brian Donlevy’s intended co-star was named as Patricia Morison. At other times, the story reports, Guts Regan was planned for Fred MacMurray, Melvyn Douglas, Don Ameche and Ray Milland. [The three new names will discussed in turn.] image: The New York Times, December 30, 1940, pg. 20 |

|

||||

| Patricia Morison could be wily and vicious, albeit in a subdued kind of way; a woman who could take charge. film source: Patricia Morison in Dressed to Kill (1946), with Edmond Breon (collector), Harry Cording (murderer), and Frederic Worlock (sharing car seat) |

|||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| Fred MacMurray could play tough repressed characters. MacMurray also played wise gentlemen in comedies and dramas, and played many love scenes. film source: Fred MacMurray in Borderline (1950), with Raymond Burr and Claire Trevor |

|||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| Also considered was Melvyn Douglas for the role of “Guts” Regan. Douglas was then well-established as a leading man, and the year prior to this 1940 news story, had starred opposite Greta Garbo in Ninotchka. We’re seeing him in the year following this report. film source: Melvyn Douglas in That Uncertain Feeling (1941), with Merle Oberon (wife) and Burgess Meredith |

|||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| In this last of three looks at a story from December 30, 1940, we’re given Ameche’s reason for refusing the role of Guts Regan. image: The New York Times, December 30, 1940, pg. 20 |

|

||||

| Stanwyck lost the role of Karen Andre for the second time, counting the Broadway production—she may have known a sharp insult to deliver to the decision-makers at Paramount. film source: Barbara Stanwyck in Meet John Doe (1941) |

|||||

| ||| | ||| | |||||

| The movie The Night of January 16th was released in 1941. Ayn Rand wrote in 1968 that only one line of her dialogue made it into the movie, and that that was “The court will now adjourn until ten o’clock tomorrow morning.” She stated also that a few character names were otherwise all of what was hers which made it into the movie. [The names of the principal characters in the movie appear in this illustration in its left-side column. A comparison with a list of the character names of the original play—which can be seen on the London Times review of the play, above, and on the programs of revival productions, shown below—demonstrates how few of the playwright’s names were retained.] image: cast and credits for the movie The Night of January 16th published at the top of the New York Times review of the film, December 19, 1941, pg. 35 |

|

|||||

| The leading lady was Ellen Drew, and we see her here playing—not Karen Andre—but Kit Lane. The character name was changed. images: (right and below) still photographs shot and distributed to publicize The Night of January 16th movie |

|

|||||

| In looking at her expression, in a situation calling for seriousness, you might think that it has that off-kilter quality of supporting players in Three Stooges comedies. Well, that’s because this movie is played as though the roles were supporting parts in Three Stooges comedies. Viewers of the movie don’t get a sense that the events are important, and they don’t even get the expertly-timed slapstick of a movie actually featuring the Stooges. | ||||||

|

This scene with a drunk has no counterpart in the play. The drunk merely turns up and leads the principal characters on a plot detour that has no bearing on later story developments. The actor playing the drunk does inject life into his scenes, for he was Cecil Kellaway, a wonderful personality whose talent would be matched nicely to an Ayn Rand role in Love Letters, where he played the caretaker. | |||||

| The leading man role was a character not in the play; he is a nephew of someone in the play, although Ayn Rand’s play never mentioned a nephew. He was played by Robert Preston, years before he wowed audiences as “The Music Man” on Broadway and in the movie. He is seen here in a 1940 film, where his co-star on the right is Doris Nolan, the original Karen Andre of “Night of January 16” on Broadway. images: Robert Preston (left) in Moon Over Burma (1940), with Doris Nolan (right) |

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

| ||| | ||| | |||||

| While this outrage was assembled in Hollywood, Ayn Rand was in New York seeking interest in a new play of hers called “Think Twice.” There will be no news clippings or film clips on this one, because “Think Twice” was never produced; no producer ever even agreed to do it. One of Ayn Rand’s characters is an independent-minded actress whose talents were misused as the leads in such passe plays as “Peter Pan” and “Little Women,” an invented tragedy called “Daughter of the Slums,” and—would you believe it?—“The Yellow Ticket.” “The Yellow Ticket,” which Fox made a strong film of in 1931, depicting a woman’s plight after the Russian government stigmatizes her, had first been a play first performed on Broadway in 1914—and Ayn Rand would have good cause to know about this: it had been produced by the very Al H. Woods who produced “Night of January 16th” twenty-one years later. images: (right top) Copyright registry log entry for Think Twice, on file at the United States Copyright Office; bottom line reads “of U. S.”; |

|

|||||

|

||||||

images: (left) The New York Times, February 3, 1914, pg. 20; |

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

This series continues on the next page.

New content © 2013, 2016 David P. Hayes

In the video counterpart to this web site, and in the video portions of the site, the Ayn Rand quotations are spoken by Susan Crawford.