| Click above to watch the content of this web site in video form. After watching the eighty-six minutes in the playlist (which consists of six segments), you will have seen all of the material on this site, except for a small number of items identified in the text portion of the web site as “Web Bonus Content and the contents of the Appendices page.” [Following playback of the six-part series, the playlist will continue with a seventh video (running under two minutes) which is not part of the series but supplements one aspect of it.] Those who prefer to read rather than listen to the narration in the video, can get the same facts by remaining on this page and continuing with the succeeding pages. Visitors who experience the content in this way won’t miss the film clips interspersed within the full video, because the film clips have been isolated for one-subject playback and have been placed between the same text passages as where the clips appear in the full video. Most citations for newspaper clippings, and all identifying information for the film clips, are omitted in the videos. Viewers of the full video who want to know the source of a particular item, should come to the text pages to obtain the desired citations. |

Actors Chosen for Ayn Rand Roles

This web site is divided into four main pages plus a page of appendices.

Use this navigation pane to go directly to a particular page.

1. • Ayn Rand’s Early Hollywood Years

• “Night of January 16th” under its original Broadway producer . . . . go there

2. • “Night of January 16th” as a movie

• We the Living adapted for Broadway . . . . go there

3. • Ayn Rand returns triumphantly to Hollywood . . . . current page

4. • Other “Night of January 16th” productions

• Juries and Jurors

• Cast ideas for Rand’s Magnum Opus . . . . go there

Appendices. Contents include: the proper title for “Night of January 16th,”

Ayn Rand’s cast choices for Atlas Shrugged,

and further information about the actors discussed in the main pages . . . . go there

| ||| | ||| | ||||

Ayn Rand Returns Triumphantly to Hollywood |

|||||

| 1943 was a great year for Ayn Rand. May 7th was publication date for her novel The Fountainhead. Before the year was out, she sold the Fountainhead movie rights to Warner Bros. and moved back to California for that movie. Warner Bros. had not been the only studio interested. They aren’t even named in this Variety item from just one month and two days after The Fountainhead was published, but image: Variety, June 9, 1943, pg. 6 |

|

||||

| Warner Bros. was good for Ayn Rand; there, she met a producer about to leave Warner Bros. and who thus soon hired her to write screenplays for him at his new independent production company aligned with Paramount. |  |

||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| In July 1944, syndicated Hollywood correspondent Hedda Hopper interviewed Ann Sheridan and reported that Sheridan was “devouring” The Fountainhead. Ann Sheridan was contracted with Warner Bros.—so she may have been reading to see herself as heroine Dominique. image: Interview of Ann Sheridan by Hedda Hopper, Hartford Courant, July 9, 1944, pg. SM8; this article also appeared the same day in the Baltimore Sun (pg. SM4) and the Chicago Tribune (pg. C3). |

|

||||

| Some 1950 clips let us see how she might have played a defiant woman emotionally indifferent to her husband. film source: Ann Sheridan in Woman on the Run (1950), with Dennis O’Keefe |

|||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| The producer who hired Ayn Rand to write for his new independent production company was Hal Wallis, and we see reported here in a July 21, 1944, piece that he was to have Ayn Rand write “The Loves of Lola Montez.” The columnist but not necessarily the producer thought of Joan Fontaine as the star. image: Hedda Hopper column (syndicated), as it appeared in Chicago Tribune, July 21, 1944, pg. 17 |

|

||||

| We’ll see how Fontaine conveyed the emotions of being in love. film source: Joan Fontaine in “Trudy” (1955), an episode of Four Star Playhouse, with James Flavin |

|||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| Two months later, it was reported that Ayn Rand was adapting Love Letters for Wallis. Unlike the “Lola Montez” project, Love Letters made it to film. What viewers of the film might not have known was that Ann Richards was originally to play the lead role eventually played by Jennifer Jones. image: The New York Times, September 18, 1944, pg. 16 |

|

||||

| Ann Richards didn’t get taken off Love Letters; instead, she was assigned a smaller role. This item says Ann Richards and Jennifer Jones are romantic rivals in the movie, but that’s questionable at best. image: Los Angeles Times, September 20, 1944, pg. 10 |

|

||||

| At Warner Bros., casting was announced for The Fountainhead: Humphrey Bogart and Barbara Stanwyck. image: The New York Times, January 20, 1945, pg. 16 |

|

||||

[The following remarks are spoken as narration during the video:] Here’s Bogart. Humphrey Bogart became a huge star with Casablanca a little over two years earlier. He was playing serious, noble, fair, resolved men. A return to the mean Bogart was years off. film source: Humphrey Bogart in a coming attractions trailer for The Big Sleep (1946), with Dorothy Malone; the scene excerpted here does not appear in the copyrighted feature film |

|||||

| ||| | ||| | |||||

| Another assignment from Hal Wallis to Ayn Rand was adapting a novel titled “The Crying Sisters.” Ann Richards was again to star. images: (right) The New York Times, January 27, 1945, pg. 15; |

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

| ||| | ||| | |||||

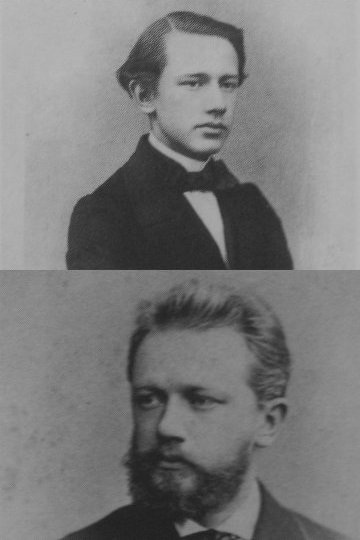

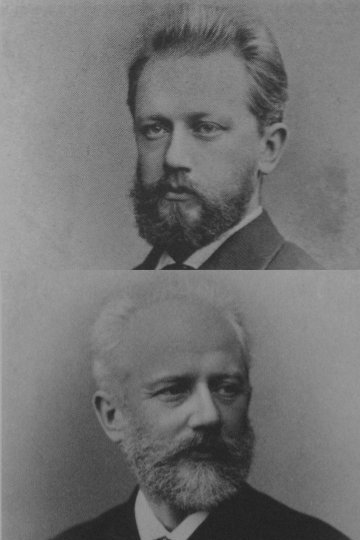

| Ayn Rand was assigned to dramatize the life of Peter Tchaikovsky. As reported in this March 22, 1945, item:— image: (right) The New York Times, March 22, 1945, pg. 19 |

|

|||||

|

—Hal Wallis planned to tell the story of the great composer, and though the article doesn’t mention it, Tchaikovsky lived his life in the same country as Ayn Rand suffered her childhood. Ayn Rand had mentioned Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto in her novel The Fountainhead, as a favorite of a young man pursuing inspiration. [In the video counterpart of this web site, the narration at this point is underscored by a recording of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony from the soundtrack of the movie Midnight Lady (1932).] |

|

||||

| A month later, it could be reported that Wallis’s Tchaikovsky film might be made with the cooperation of Vladimir Horowitz and Leonard Bernstein. images: (below) Los Angeles Times, April 27, 1945, pg. A3; |

|

|||||

|

||||||

| Vladimir Horowitz had proven extremely popular, his concerts heard on nationwide radio, his performances with conductor Arturo Toscanini raising fantastic amounts of money for the United States war effort. images:

Atlanta Constitution, April 25, 1943, pg. 11-C; |

|

|

||||

|

|

|||||

| In March 1944, Bernstein had made himself a national reputation as the 25-year-old assistant conductor who on a moment’s notice and without rehearsal conducted a symphony program on a radio broadcast when the planned conductor took sick. images: Baltimore Sun, March 12, 1944, pg. A10 |

||||||

| ||| | ||| | |||||

| A year after Ayn Rand was assigned to write, a report would appear, in October 1946, that Wallis wanted James Mason to play the composer and that Wallis would film in England. Mason was then a rising British star who was still three years from his first American film. His decade of huge international stardom would be the 1950s. images: (left) James Mason; |

|

|

||||

| ||| | ||| | |||||

June 1945 marked the first time that the name of Ayn Rand appeared onscreen and in ads as a screenwriter. She and writer Robert Smith shared credit for the screenplay based on Smith’s story. Rand said privately that the movie also reflected the influences of the director and the producer.

|

||||||

| ||| | ||| | |||||

| images: from the press book for You Came Along prepared by Paramount |

|

|

||||

| ||| | ||| | |||||

| Lizabeth Scott became a star in this, her first film. image: from the movie’s press book |

|

|||||

| In this film clip from the year after You Came Along, producer Hal Wallis again showcased Lizabeth Scott’s ability to play a take-charge woman who nonetheless is willing to recognize her emotional vulnerability. film source: Lizabeth Scott in The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946), with Van Heflin |

||||||

| ||| | ||| | |||||

| Top-billed was Bob Cummings in the role of Bob Collins. |  |

|||||

[The following remarks are spoken as narration during the video:] The character name “Bob Collins” on the door and his wearing a military uniform may make you think you’re watching Bob Cummings in You Came Along, but actually this is from Cummings’s 1950s television sitcom. He brought back his earlier character name, and continued his good-natured conviviality and his comical voice mannerisms. film source: Robert Cummings in The Bob Cummings Show (also shown as Love That Bob), with Ann B. Davis |

||||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||||||||

| Two months after You Came Along was released, Love Letters reached theaters, and for the first time Ayn Rand’s name appeared as sole screenwriter. Love Letters had completed filming two months prior to You Came Along doing so, but was held back while the more topical You Came Along was rushed to screen a month after Germany surrendered in WWII. As you see here, Paramount’s advertising materials for Love Letters touted—in conjunction with their screenwriter’s name—that she was the author of The Fountainhead, stating that fact under her name. Although the book had been published two and a quarter years earlier, in 1945 The Fountainhead appeared on more bestseller lists than it had the prior two years. images: ads for Love Letters in Paramount’s press book for the movie. |

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||||||||

|

Come October, several newspapers had fun reporting that Hal Wallis had bought screen rights to the play “Beggars Are Coming to Town” several weeks before its opening. Less fun was had by audiences inside the theater, condemning the play to a run of twenty-five performances. For this Wallis paid $100,000 and guaranteed percentages of the profits to the play’s backers. |

|

|||||||||

image: The New York Times, October 5, 1945, pg. 27 |

image: The New York Times, October 29, 1945, pg. 16 |

||||||||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||||||||

|

The New York Times review of the play indicates that this is the type of play Ayn Rand would regard as the opposite of what her aesthetic theories regards as good fiction: a nostalgic gangster story where the gangsters talk instead of shoot, and where a “leggy cigarette girl” is the lead woman character, removing an opportunity for a woman character who is intelligent. So who did Hal Wallis get to write a screenplay?— image: The New York Times, October 29, 1945, pg. 16 |

||||||||||

| —Ayn Rand! This announcement appeared in Variety, December 3, 1945. image: Variety, December 3, 1945, pg. 11 |

|

||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Eddie Albert |

On February 4, 1946, a news item reported that Eddie Albert had been hired for the lead, and in May “Beggars Are Coming to Town” was named as one of three projects which Wallis was planning, but “Beggars Are Coming to Town” then sank from mention. Eventually, the lead role went to Burt Lancaster, the film was released two years after the announcement about Eddie Albert, and the title had been changed to I Walk Alone. Note: The referenced news item about Eddie Albert is in Los Angeles Times on page 9. |

|

|||||||||

|

Lizabeth Scott and Kirk Douglas also starred. Charles Schnee, Robert Smith and John Bright were credited for screenwriting and adaptation. |  |

|||||||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||||||||

| In January 1946, five months after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought the world into the atomic age, Hal Wallis was rushing to make a film on the development of the atomic bomb. Its title: “Top Secret.” Ayn Rand was assigned to write, working from material supplied by a contact in the nation’s capitol. images: two sections of an article in Daily Variety, January 14, 1946, pg 11 Note: Groves’s participation in the two productions was reported as follows: “It was very hush-hush, but Maj. Gen. Leslie R. Groves, who was in charge of the atomic bomb project, spent a day on the Metro [ |

|

||||||||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||||||||

|

Paramount’s plans for its Hal Wallis production about Tchaikovsky hit a snag when a rival production on the same subject was announced. Normally, Paramount didn’t have to worry about competition from Monogram Pictures, but this time both were planning a Tchaikovsky film. image: (left) The New York Times, October 3, 1946, pg. 38 Monogram Pictures was in the business of low-budget movies. This trade-publication ad announcing its 1949 releases shows that none were destined for awards. image: (right) Motion Picture Almanac, 1949-50, pg. 193 |

|

|||||||||

| However, Monogram had recently resolved to make better films, and chose the studio name Allied Artists on these films so that the name Monogram would not appear on advertising. This trade ad lists Song of My Heart, the eventual title of the Allied Artists Tchaikovsky film. image: Motion Picture Almanac, 1948-49, pg. 257 |

|

||||||||||

| Variety let its readers know that Allied Artists was Monogram in its review of this fictionalized biography of Tchaikovsky, shown to the film trade in late 1947 and released to the public the next year. Produced at a cost of $600,000, it was twice as expensive as a major-studio low-budget film and six times as costly as a standard Monogram picture. images: review of Song of My Heart, in Weekly Variety, November 5, 1947, referring to “Monogram’s upper-bracket Allied Artists”; |

|

|

|||||||||

|

At Hal Wallis’s studio, his Tchaikovsky project, like the Lola Montez before it, never went before the cameras. | ||||||||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||||||||

| The Fountainhead was delayed. In a January 26, 1947, interview, Clark Gable stated that he read The Fountainhead in 1943 and immediately wanted to play Roark. Unfortunately, his studio— image: Interview of Clark Gable by Eleanor Harris, Los Angeles Times, January 26, 1947, pg. E6; this interview also appeared the same day in Baltimore Sun, pg. WM6, and in New York Herald Tribune. |

|

||||||||||

| Gable when renegotiating his MGM contract the year prior to that interview was reported to be attempting new terms allowing him to do The Fountainhead at Warner Bros. while also working at MGM most of each year. image: Daily Variety April 16, 1946 |

|

||||||||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||||||||

| In what could have become an enormously expensive effort by |

|

|

|||||||||

| Alan Ladd resembles the Howard Roark of the comic-strip version of The Fountainhead which appeared in newspapers for thirty days from 1945 into 1946. The characters’ appearances had Ayn Rand’s approval. Alan Ladd was Paramount’s resident tough-guy actor as Humphrey Bogart was Warners’. film source: Alan Ladd in My Favorite Brunette (1947), with Bob Hope Notes: “For the role of Roark, Humphrey Bogart and Alan Ladd were considered”—Ayn Rand: a Sense of Life (“A Companion Book to the Feature Documentary”), by Michael Paxton (Gibbs-Smith, 1998), pg. 130. “Veronica Lake told people that Ayn had written the part for her because she had Dominique’s hairstyle.”—ibid, pg. 132. The same statements are made in the narration of the documentary film of the same name, released theatrically 1998 and later available on DVD. |

|||||||||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| Two years and four months after the first stories about Hal Wallis planning “The Crying Sisters,” this story appeared about actor Mickey Knox being considered for it. image: Los Angeles Times, May 28, 1947, pg. A7 |

|

||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| The last of the Hal Wallis projects we’ll discuss—potential or made—is “House of Mist.” It would have a fairy-tale atmosphere to tell a story of romance, suitable to be enjoyed by adults, and plans were considered to film in England. British performers may well have made up most or all of the cast had the film been made. image: Weekly Variety November 5, 1947, pg. 7 |

|

||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| On March 29, 1948, news was reported which should have been decided long before: The Fountainhead would star Gary Cooper. This item mentions Lauren Bacall as a possible Dominique. She was a major Warner Bros. star, and had a tough demeanor. Had Roark not been recast, she would be repeating already-established screen chemistry. Before 1948 was over, she had starred four times opposite Humphrey Bogart, for three years now her off-screen husband. image: The New York Times, March 29, 1948, pg. 18 |

|

||||

| May 5 brought to Fountainhead news that Raymond Massey was cast as Gail Wynand. Patricia Neal is mentioned in passing here, as though already set. She played Dominique. image: Christian Science Monitor, May 5, 1948, pg. 5 |

|

||||

| Before May was over, other actresses were reported in the running for the Dominique role. Lauren Bacall and Joan Crawford had been mentioned. Barbara Stanwyck is quoted saying that she’ll hear that she’s on and she’s off. Barbara Stanwyck was the one person who convinced Warner Bros. to acquire The Fountainhead when it was an unknown property. |

|

||||

| On - off - on - off. You can imagine how Stanwyck felt. film source: Barbara Stanwyck in Meet John Doe (1941), with James Gleason |

|||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| Would Joan Crawford work as Dominique? Here’s Joan Crawford when confronted. film source: Joan Crawford in Rain (1932) |

|||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

|

A week before shooting began, in a June 21st story, Patricia Neal is reported to have the lead, in a headline statement and report without ambiguity. image: The New York Times, June 21, 1948, pg. 18 The June 21st story continues by mentioning actresses who didn’t get the role: Crawford, Stanwyck, Bacall. Included with them is a name we haven’t mentioned before: Bette Davis. image: The New York Times, June 21, 1948, pg. 18 |

|

|||

| Bette Davis eight years earlier had been intrigued by the role of Kira in “The Unconquered,” but at the advice of her management declined to do the play. We see her discuss a 1950 role which fascinated her. film source: Bette Davis in a coming attractions trailer for All About Eve (1950); the scene excerpted here does not appear in the copyrighted feature film |

|||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| Eleanor Parker had impressed people with her performance in the Bette Davis role in the 1946 remake of Of Human Bondage, and went on to more lead roles. A biography of Gary Cooper reports that Parker was considered to play Dominique. image: (right) from “Gary Cooper: American Hero,” by Jeffrey Meyers (1998), pg. 216 |

|

|

|||

| In this 1955 film, Eleanor Parker shows that she can convey headstrong emotions—even though the thoughts she expresses would never be spoken by an Ayn Rand heroine. film source: Eleanor Parker in The Man With the Golden Arm (1955), with Kim Novak [The narration remark stated at the end of the video is not printed here, so as not to ruin the scene for those who haven’t seen it.] |

|||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||

| Barbara Stanwyck discussed her removal from the Fountainhead cast sixteen years afterward, and an obituary carried her explanation that director King Vidor rejected her. Stanwyck’s portrayal of Dominique would have reunited her with Gary Cooper after two 1941 films. image: Washington Post, January 22, 1990, pg. B1 |

|

|

|||

| Seeing Stanwyck express love to Cooper in the following 1941 scene lets us see how she may have played Dominique to his Roark. film source: Barbara Stanwyck in Meet John Doe (1941), with Gary Cooper |

|||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||||||||||||||

|

Stanwyck had also been announced to play The Fountainhead opposite Humprey Bogart. How they would play opposite each other was also captured on film, this time in The Two Mrs. Carrolls. This was not a coincidence. When The Fountainhead couldn’t go before the cameras in early 1945 owing to a war-related shortage of building materials necessary for sets, Warner Bros. shifted their two lead Fountainhead actors to The Two Mrs. Carrolls. images: still photograph and poster of Humphrey Bogart and Barbara Stanwyck in The Two Mrs. Carrolls; Note: Alexis Smith—the other star named on the poster—is discussed later. |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||||||||||||||

| King Vidor completed shooting of The Fountainhead two days ahead of schedule and $200,000 under budget. image: Daily Variety, September 24, 1948, pg. 1 |

|

||||||||||||||||

| ||| | ||| | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

This series continues on the next page.

New content © 2013, 2016 David P. Hayes